Solargraphy

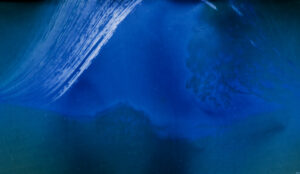

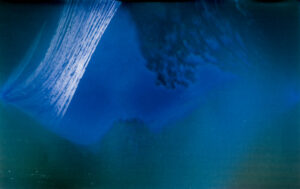

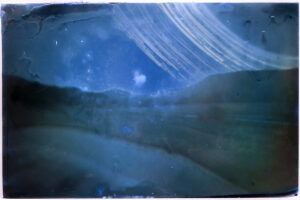

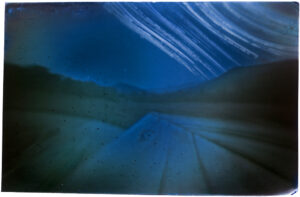

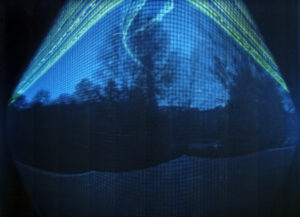

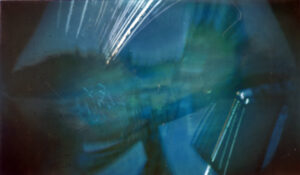

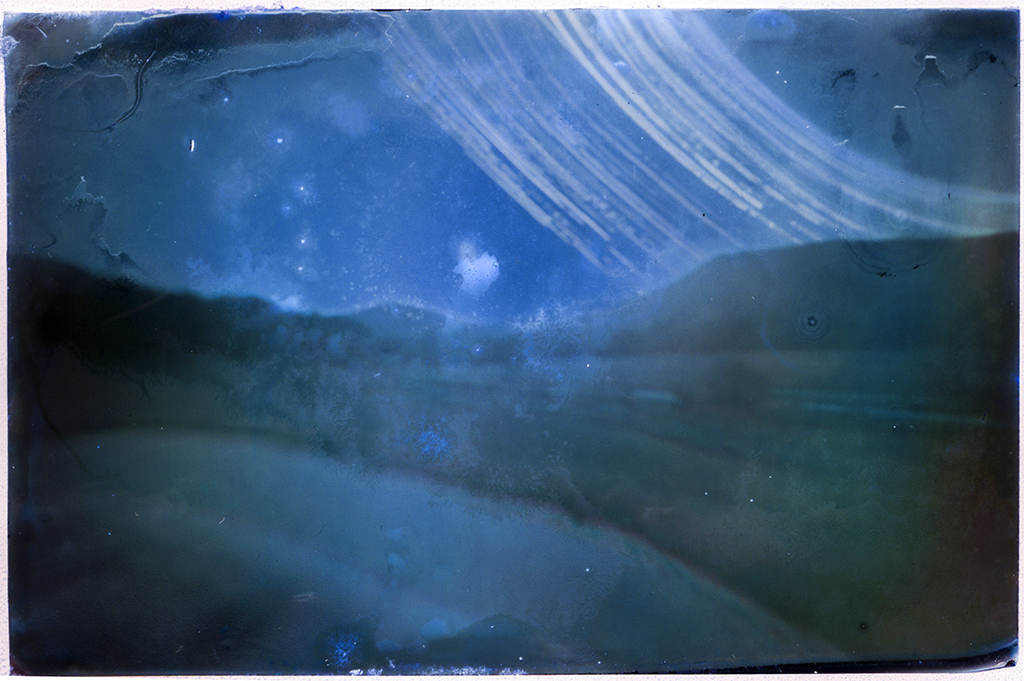

Solargraphy is a type of pinhole photography that’s all about capturing the sun’s path across the sky over long periods—anywhere from days to months, or even years. The wild part? It doesn’t need any chemical processing. Over time, a latent negative image just appears on the paper negative, like magic. I use black-and-white photo paper as negatives, then scan the images. After that, I reverse them from negative to positive in Photoshop, making any tweaks or corrections as needed. But the look of these images isn’t some Photoshop trick—it’s the nature of solargraphy itself.

I make my cameras out of all sorts of random containers: 35mm film canisters, oatmeal tubes, cookie tins, Altoids tins… you name it. Pretty much anything that can be made light-tight can become a camera. The cameras I used for the solargraphs here were made from hemp protein containers. They’re great for solargraphy, but the shakes? Not so much. Blech!

How Solargraphy Works

Solargraphy is surprisingly simple, and that’s part of its charm. It all starts with a pinhole camera—no fancy lenses, no batteries. Just a light-tight container with a tiny hole in it, and a piece of photosensitive paper inside. When you place the camera in position, the light from the sun slowly streams through the pinhole and hits the paper, recording the sun’s path as it moves across the sky over days, weeks, or even months.

The exposure is long, so you set it up and let time do the work. The sun’s movement creates graceful arcs on the paper, capturing the way it rises and sets each day. What’s even cooler? You don’t need to develop the photo in a darkroom. Over time, an image naturally appears on the paper. I scan the paper, reverse it from negative to positive in Photoshop, and make a few adjustments, but the final look is all about the solargraphy process itself.

It’s a low-tech, low-maintenance way to make art that’s all about the passage of time and the natural world.

Capturing Solargraphs

Once your pinhole camera is ready, find a good spot with a clear view of the sky where the sun’s path will be visible. Rooftops, open fields, or even a windowsill can work. Just make sure the camera won’t be moved during the exposure—it needs to stay in the same position for days, weeks, or even months.

Once the camera is in place, you let it sit and let nature do the rest. The sun will create long, arcing trails across the sky, which will slowly appear on the paper inside the camera. The longer the exposure, the more trails you’ll see. You don’t need to check on it until you’re ready to stop the exposure and see what you’ve captured. That’s it!

Processing Solargraphs

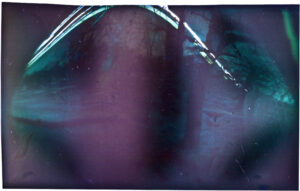

One of the best things about solargraphy is that no chemicals are needed to develop the image. Once your exposure is done, carefully open the camera in subdued light to avoid overexposing the photo paper. The image will already be visible on the paper, thanks to the long exposure time.

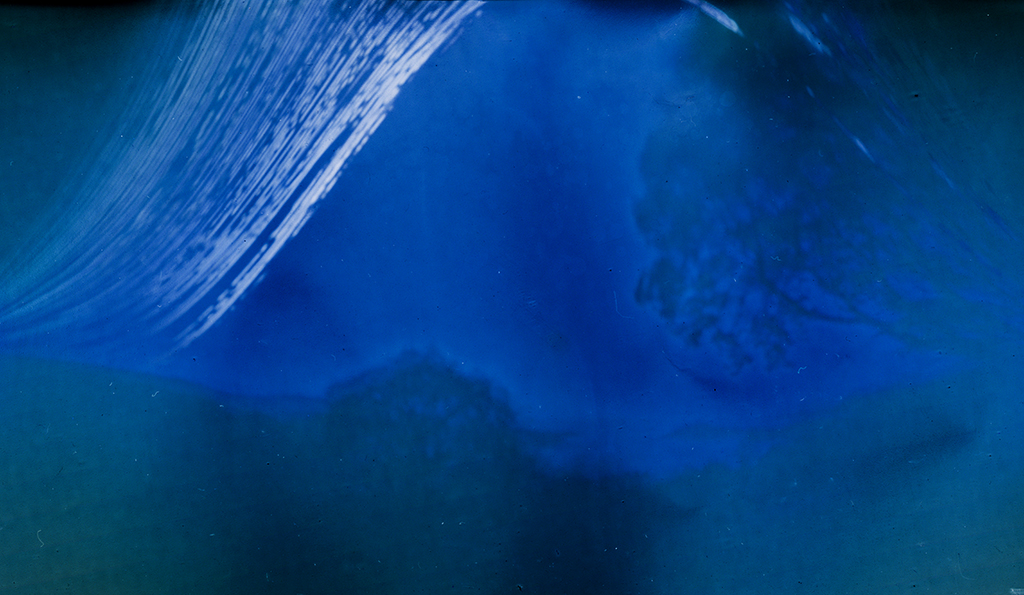

Once you’ve removed the paper, I recommend scanning it right away to preserve the image digitally. In Photoshop, I reverse the image from negative to positive and make adjustments as needed. Solargraphs often appear in beautiful shades of blue and other cool tones, a natural result of the sun’s interaction with the photosensitive paper over time.

Why I Love Solargraphy

Solargraphy is a process that really speaks to my love of combining the old and the new. There’s something magical about using a simple, handmade pinhole camera to capture the passage of time.

Solargraphy feels like a perfect balance between my passion for vintage photography techniques and my curiosity about how we can use them in new ways. The experimental and unpredictable nature of solargraphy makes it fun. I never know exactly what the final image will look like until I open the camera—each photo is a unique result of light, time, and the weather.